Why Hydrilla is a “Top-Threat” Species for Seaplanes: Hydrilla is among the most invasive aquatic plants wreaking havoc on U.S. waterways, posing a direct and significant threat to seaplane pilots and operations. This plant’s aggressive growth, dense mats, and ease of spread interfere seriously with seaplane safety and efficiency. This article breaks down why Hydrilla is a top-threat species for seaplanes, detailing its biology, impacts, management, and practical prevention steps, with clear insights both for newcomers and seasoned professionals in water aviation and aquatic ecosystem management.

Table of Contents

Why Hydrilla is a “Top-Threat” Species for Seaplanes?

Hydrilla is a formidable invasive species that significantly challenges seaplane operations, aquatic ecosystems, and regional economies. Its biological resilience, rapid growth, and density make it especially hazardous for water-based aviation. Awareness, operational best practices, and cooperative management efforts among pilots, environmental agencies, and communities are essential to slowing Hydrilla’s spread and preserving healthy, navigable waterways. By understanding this threat and implementing prevention and control strategies, seaplane operators can protect both their aircraft and the integrity of America’s precious aquatic environments.

| Topic | In-depth Details |

|---|---|

| Scientific Classification | Kingdom: Plantae; Family: Hydrocharitaceae; Genus: Hydrilla; Species: verticillata |

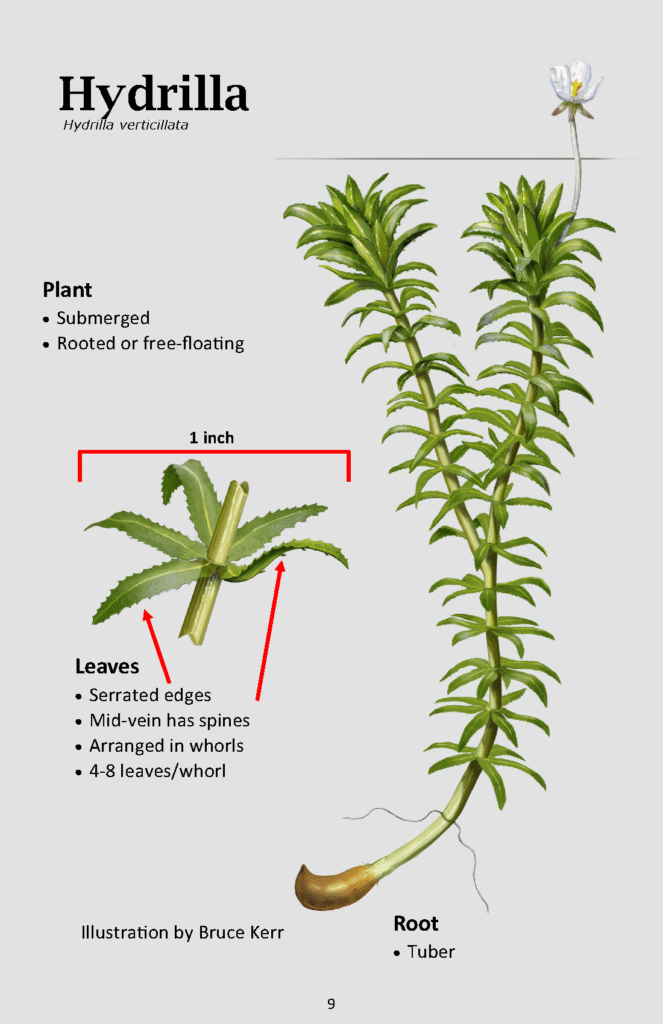

| Physical Traits | Stems up to 3m; leaves in whorls of 3-12 with serrated edges and spines on veins; grows in 1 inch to 20 feet depth |

| Growth Conditions | Tolerates wide water quality range; optimum growth at 20-27°C; moderate salinity tolerance up to 7ppt |

| Reproduction | Sexual via unisexual flowers; asexual via tubers and fragmentation; rapid biomass doubling in warm months |

| Geographic Spread | Over 30 US states; native to Asia, Central Africa; invasive globally |

| Impact on Seaplane Ops | Props and rudders clogged; surface waters blocked; maintenance burden increased; spread via equipment transfer |

| Environmental Effects | Blocks sunlight; lowers dissolved oxygen; alters water chemistry; smothers native plants; causes fish kills |

| Economic Impact | Tourism and recreation losses; property value decline; damage to water infrastructure; costly management programs |

| Management Techniques | Herbicides (fluridone, endothall); biological control agents; mechanical harvesting; drawdowns of water levels |

| Prevention Advice | Clean gear thoroughly after every landing; drain bilge water away; avoid moving between infested and clean waters |

| Official Reference | National Invasive Species Information Center |

What is Hydrilla? Why Pilots Should Pay Attention

Hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillata), belonging to the plant kingdom, family Hydrocharitaceae, is a submerged aquatic perennial native to Asia and parts of Central Africa. It has been present in US waters since the 1960s and is now found in over 30 states, including Florida, Texas, New York, and Michigan.

Hydrilla typically grows up to 3 meters (around 10 feet) in stems that are just 1 millimeter thick but highly branched. Leaves form in whorls of 3 to 12 at nodes along the stems and have sharp serrated edges, with tiny spines on the veins underneath. This configuration, coupled with its ability to grow in water from shallow inches to depths of 20 feet, makes it particularly resilient.

Hydrilla reproduces both sexually through unisexual flowers and asexually through tubers and fragmentation, allowing populations to explode rapidly in favorable conditions. Its tolerance for a variety of water conditions from acidic to eutrophic—and moderate salinity levels—enables it to thrive in many freshwater habitats across climates from tropical to temperate.

For seaplane pilots, these features spell trouble: the plant’s dense mats clog propellers, grab onto floats and hulls, and cover surface waters crucial for takeoffs and landings. The fast-growing nature and resilience ensure Hydrilla can create operational hazards quickly and spread via seaplane equipment to uninfested waters, spreading the invasive threat.

How Hydrilla Disrupts Seaplane Operations?

Hydrilla’s rapid and dense growth means it can blanket the surface or float just beneath, trapping seaplane propellers and rudders in a tangle that seriously hinders movement. Pilots face the constant nuisance and danger of having to stop mid-operation to clear out vegetation, sometimes multiple times, increasing operational risk and flight time.

Water surfaces densely covered by Hydrilla become unpredictable zones with reduced visibility and increased drag, complicating critical phases of flights—takeoff and landing. This damage to equipment translates directly to added maintenance costs and potential flight hazards.

The sticky problem gets worse as Hydrilla fragments attach to aircraft floats, motors, and trailers. Pilots inadvertently become carriers, transporting these fragments from infested water bodies to pristine lakes and rivers across states, accelerating the species’ invasion and environmental damage.

Environmental Impact: The Bigger Picture

Hydrilla’s aggressive growth profoundly alters freshwater ecosystems:

- Shading Effect: Thick mats of Hydrilla block sunlight, killing native submerged plants that provide habitat and food for aquatic animals.

- Oxygen Depletion: With heavy growth, oxygen levels dip dramatically, especially overnight, since Hydrilla consumes oxygen during respiration, leading to fish kills and stressed aquatic life.

- Water Chemistry Alteration: Hydrilla can raise water temperature and pH, disrupting natural conditions that native species depend on.

- Physical Blockage: Slow water movement caused by dense mats diminishes the health of the ecosystem and complicates water-based human activities.

- Loss of Biodiversity: Evidence shows monocultures of Hydrilla replace diverse native plant communities, reducing overall ecosystem resilience and health.

Economic Consequences: Counting the Costs

Hydrilla’s ecological effects translate into economic losses too:

- Tourism and Recreation: Popular recreation spots bog down due to dense weed growth, deterring boating, fishing, and swimming; communities dependent on lake tourism face declines in income.

- Property Values: Waterfront properties lose value because access and water quality suffer, leading to lower tax revenues that support local services.

- Water Infrastructure Damage: Hydrilla invades and clogs canals, dams, and water intake structures, increasing maintenance costs for utilities and municipalities tasked with managing water resources.

- Seaplane Industry Impact: Fewer safe water sites and increased equipment maintenance costs impact commercial and recreational seaplane activities, potentially hurting local economies relying on these transport routes.

Advances in Hydrilla Management

Hydrilla is tough to control, but science and technology are making progress:

- Chemical Control: Herbicides like fluridone and endothall are standard treatments. Fluridone treats more slowly but longer-lasting; some resistant strains exist, so it’s often part of integrated management.

- Biological Control: Research into natural predators, such as the leaf-mining fly and certain fungal pathogens, shows promise as environmentally friendlier long-term solutions.

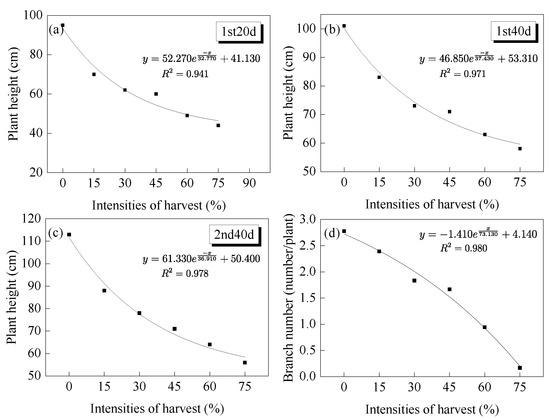

- Mechanical Harvesting: Physically removing mats helps temporarily but risks spreading fragments if not done carefully.

- Water Drawdowns: Lowering water levels in winter exposes tubers to freezing and drying, reducing populations, but is only feasible in select locations.

- Monitoring and Early Detection: Regular surveys by environmental agencies help curtail outbreaks early and target management more effectively.

Practical Prevention Strategies for Seaplane Pilots

Pilots and operators are frontline defenders against Hydrilla’s spread:

- Meticulous Cleaning: After every water landing, thoroughly scrub floats, hulls, propellers, and rudders to remove plant fragments.

- Drain and Dispose Properly: Empty bilge water and other compartments away from water bodies to prevent reintroduction.

- Avoid Cross-Contamination: Don’t fly directly between infested and uninfected water bodies without cleaning.

- Report New Infestations: Contact local invasive species programs when new Hydrilla sightings occur to facilitate rapid response and containment.

Avoiding Fines: A Complete Guide to AIS Transport Laws for Pilots

Are Seaplanes “Watercraft”? Understanding the Legal Gray Area in AIS Law

State-by-State AIS Regulations: A Seaplane Pilot’s Compliance Guide