Are Seaplanes “Watercraft”? When it comes to seaplanes, things can get a little tricky. Many folks wonder, “Are seaplanes actually considered watercraft or vessels when they’re on the water?” Well, if you’ve ever watched a seaplane take off or land on a lake or river and thought it was just a plane, you’re not alone. The reality is, legally speaking, seaplanes often skate a gray line, especially when it comes to laws about Aquatic Invasive Species (AIS) and navigation rules on water. Let’s break this down in a way that’s easy to understand, mixing some solid facts with real-world advice for everyone—from first-timers to pros.

Table of Contents

Are Seaplanes “Watercraft”?

Seaplanes are fascinating aircraft that blur the line between aviation and maritime worlds. Their unique ability to operate on water places them squarely in a legal gray zone, especially regarding vessel classification and aquatic invasive species laws. By understanding how seaplanes fit both into aviation and maritime legal frameworks, pilots and operators can stay safe, compliant, and environmentally responsible. From securing the right licenses to navigating state laws and AIS rules, every step helps keep the skies and waters safer—for pilots, communities, and ecosystems alike.

| Topic | Key Point | Example / Stat |

|---|---|---|

| Seaplane Definition | Aircraft designed to operate on water surfaces | Includes floatplanes and flying boats |

| Legal Status on Water | Treated as vessels or watercraft under maritime laws when on water | Must follow U.S. Coast Guard navigation rules |

| State Law Variations | Some states exclude seaplanes from vessel definitions, affecting rules | Michigan: no inland lake use except for over 30 miles transport |

| Aquatic Invasive Species | Seaplanes must comply with AIS laws, requiring inspections and permits | Washington requires AIS permits before seaplanes use on lakes |

| Pilot Licensing | Must have seaplane rating in addition to regular pilot’s license | Different training for single-engine vs multi-engine seaplanes |

What Exactly Is a Seaplane?

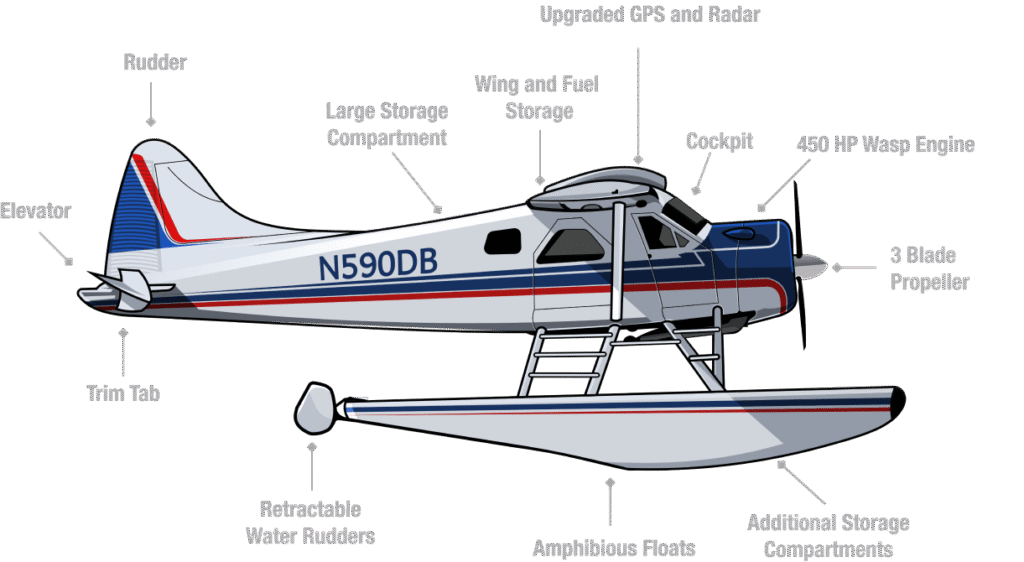

A seaplane is a specialized type of aircraft designed to take off from and land on water surfaces. These planes usually have floats or hulls that make water operation possible, allowing them to land on lakes, rivers, and coastal waters. This unique ability makes them invaluable for reaching places where land runways don’t exist, such as remote wilderness areas, islands, and regions with limited infrastructure.

Seaplanes come mainly in two forms: floatplanes, which have pontoons or floats attached under the fuselage, and flying boats, where the fuselage itself acts as a hull for water operations. Some are amphibious, equipped with retractable wheels to operate on both land and water surfaces.

Seaplanes serve diverse roles, including passenger transport, tourism, firefighting, search and rescue, scientific research, and law enforcement. Thanks to these multi-functional uses, they continue to be an essential part of aviation, particularly in regions like Alaska, the Pacific Northwest, and Florida.

A Detailed History of Seaplanes

The concept of aviation from water dates back to the late 19th century. While the Wright brothers made their historic powered flight in 1903, early aviation pioneers quickly realized water could offer a great landing platform when runways were scarce.

In 1876, French inventor Alphonse Pénaud filed the first patent for a “flying machine” with a boat hull. Later, Austrian Wilhelm Kress attempted to build one of the first floatplanes in 1898, although it never successfully took off.

The first powered seaplane flight was carried out in 1910 in Marseilles, France, by Henri Fabre, who flew his “Hydravion” equipped with floats designed for water takeoff and landing. American aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss further advanced seaplane design in 1911 and 1912, developing floatplanes and flying boats that earned him the first-ever Collier Trophy for aviation achievement.

Seaplanes saw significant development during World War I and World War II. They were used for maritime patrol, reconnaissance, and transportation where operating from water was strategically advantageous. Post-war, the growing number of airports shifted commercial aviation towards land planes, but seaplanes retained their role in niche markets like firefighting and travel in hard-to-reach locations.

The innovations during this early period, such as the “Felixstowe notch”—a hull design element enhancing takeoff performance—shaped seaplane technology that survives in modern designs.

Are Seaplanes “Watercraft”?: The Legal Perspective

Here’s the deal — when a seaplane is in the water, it’s generally viewed as a vessel or watercraft under most U.S. laws. The U.S. Coast Guard treats seaplanes just like boats once they hit the water, meaning they must follow maritime navigation rules such as right-of-way, speed limits, and proper lighting. This maritime status triggers a complex web of legal obligations.

For example, regulations require seaplanes to wear life jackets, follow navigation rules like yielding to larger vessels, and avoid creating wakes that could endanger smaller boats or shorelines. Notably, this vessel classification applies only while the seaplane is physically on the water; in the air or on land, aviation rules take precedence.

Seaplanes also fall under admiralty law during water operation, entitling them to protections and legal standings similar to ships. This classification means seaplane operators share liability responsibilities for accidents and pollution incidents akin to boat operators.

Variability in State Laws

While federal maritime law covers many aspects of seaplane operations, states differ significantly in how they regulate seaplane use, especially on inland waterways. Some states exclude seaplanes from vessel definitions, limiting their operation, while others include them fully.

- Michigan restricts seaplane use on inland lakes unless traveling over 30 miles for point-to-point transport, due to local safety and environmental concerns.

- Massachusetts bans seaplane landings at public access points on some lakes, prioritizing recreational boaters and shoreline residents.

- Oregon typically treats seaplanes like boats on waters open to motorboats but requires state aviation authority approval for some operations.

These differing rules mean pilots must research before flying into new states—violations can lead to hefty fines or bans. Local knowledge, such as seasonal restrictions, no-wake zones, and wildlife protections, also play a major role in operational planning.

The Role of Aquatic Invasive Species (AIS) Laws

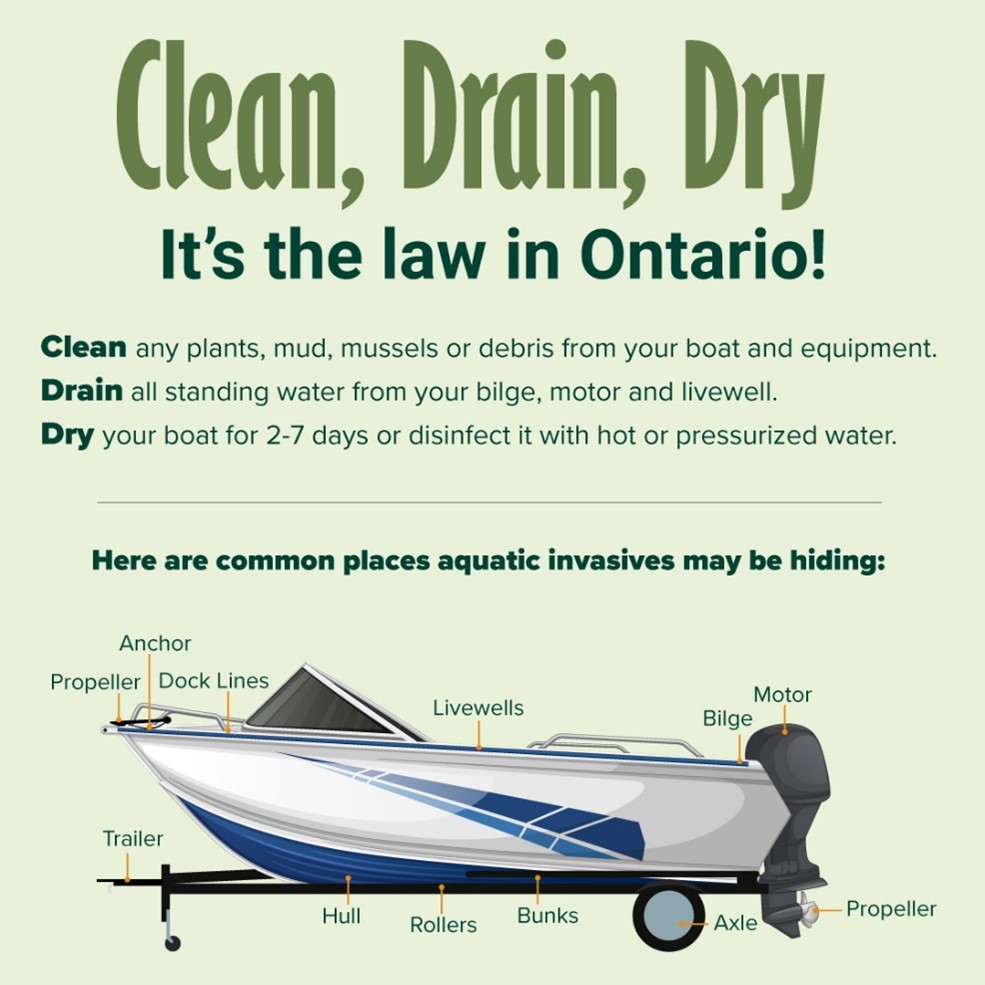

One of the biggest eye-openers for seaplane pilots today is the increasing impact of Aquatic Invasive Species (AIS) laws. AIS are organisms like zebra mussels or invasive plants that hitch rides on boats’ hulls and gear, devastating native ecosystems, fisheries, and water infrastructure.

Seaplanes share this risk. Their pontoons, hulls, and bilges can trap invasive species, making seaplanes potential carriers between water bodies. Many states have implemented laws that treat seaplanes like boats for AIS regulatory purposes.

Here’s what that looks like in practice:

- Before launching in certain states such as Washington, Illinois, and Minnesota, seaplane owners must obtain AIS inspection certificates.

- Pilots must inspect and thoroughly clean their aircraft to remove all aquatic plants, animals, and mud.

- Some states demand drying times or use of approved cleaning stations to ensure no invasive species survive.

- Failing to comply can result in fines—Washington can fine offenders up to $1,000—and harm ecosystems critical to local economies and recreation.

By following these AIS protocols, seaplane operators become guardians of the waters, balancing their mobility with environmental responsibility.

What It Means for Seaplane Pilots and Operators?

Seaplane flying isn’t just about hopping around on lakes and coasts — pilots have a handful of unique responsibilities:

1. Get the proper pilot certifications

Unlike flying a standard land plane, piloting a seaplane requires additional training and licensing. The FAA mandates seaplane ratings to ensure pilots understand water takeoff and landing dynamics, taxiing, docking, and emergency procedures. Training differs for single-engine and multi-engine seaplanes and covers both flight skills and maritime regulations.

2. Follow maritime navigation rules

Seaplane operators must navigate respectfully among boats and other watercraft, maintaining safe speeds and obeying right-of-way rules. Just like being behind the wheel on water, pilots need to watch for swimmers, other vessels, and environmental markers like buoys and no-wake zones.

3. Check local and state laws before landing

Since many waterways have specific restrictions, pilots need to research and comply with state and local ordinances that can restrict or ban seaplane landings, especially in recreational or protected areas. Advance planning and communication with marina or port authorities are smart practices.

4. Rigorous AIS compliance

Cleaning, inspecting, and sometimes reporting AIS compliance is a non-negotiable. Keeping your seaplane clean protects fragile aquatic ecosystems and demonstrates responsible piloting.

5. Equip proper safety gear

Pilots need to have life jackets, signal devices, and emergency equipment on board. Since seaplanes operate at the airy-water interface, being ready for both aviation and marine emergencies is crucial.

Seaplanes and Environmental Responsibility

Because seaplanes often touch down in ecologically sensitive areas, environmental care goes beyond legal compliance. Pilots should take actions like using eco-friendly lubricants, minimizing fuel spills, avoiding no-wake areas to protect shorelines, and respecting wildlife habitats during breeding or migration seasons.

This conscientious approach helps seaplane operations support local economies via eco-tourism and transport without jeopardizing the natural beauty that attracts pilots and passengers alike.

Navigating Insurance and Liability

Seaplanes have a double identity legally. This dual nature affects insurance needs:

- Aviation insurance typically covers aircraft operation hazards such as mechanical failure or crash.

- Marine liability insurance covers incidents on water, including collision damage or environmental cleanup costs.

Pilots and owners should secure combined or specialized policies that reflect both aviation and maritime risks to avoid unwelcome gaps.

![Case Study How [Lake Association] Partners with Pilots to Stop AIS](https://seaplanesandais.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Case-Study-How-Lake-Association-Partners-with-Pilots-to-Stop-AIS-300x169.jpg)